The Church

The Christian Church was at first an urban phenomenon which only later spread to the rural areas. It was composed mainly of people from what we would call today the “middle classes” of society. It is not true that Christianity gained its foothold in the world primarily among uneducated and backward people who were looking for heavenly consolation in the face of oppressive and unbearable living conditions on earth.

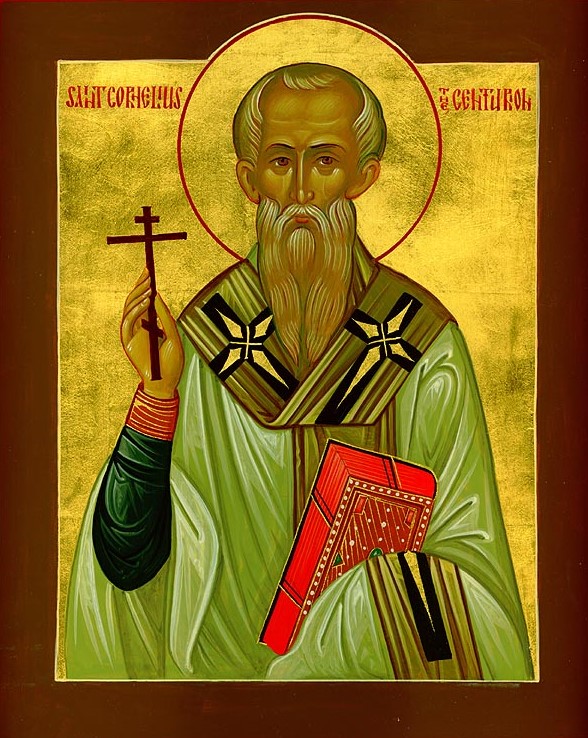

The most important decision the Church had to make during the first century was whether non-Jewish people (Gentiles) could be received into the Church by faith in Christ without being required to follow the ritual requirements of the Mosaic Law, including circumcision. Based on Saint Paul’s understanding of the Old Testament, and on Saint Peter’s testimony about how the Roman centurion Cornelius and his household received the Holy Spirit even while Peter was still speaking to them (Acts 10 and 11), the first council of the Church, held in Jerusalem in about 49 A.D., decided that Gentile converts would not be subject to the Mosaic Law (Acts 15). Held under the leadership of Saint James, the Brother of the Lord and the first Bishop of Jerusalem, this council is considered the prototype of all subsequent Church councils.

While the Christian Church entered Roman imperial society “under the veil” of Judaism, quite soon it became separated from the Jewish faith. The Church embraced all those, of whatever ethnic background, who through belief in Jesus as Lord and Christ, and through repentance from sin, were incorporated into Christ’s Body, the Church, through Baptism. After Baptism, with the laying on of hands of an Apostle or one ordained by an Apostle, the new Christians received the gift of the Holy Spirit (see Acts 2.37–39 and 8.14–17), and then participated in the celebration of the Lord’s Supper, the Holy Eucharist.

The separation of the Church from Judaism was made sharper when the Roman army in 70 A.D. crushed the revolt of the Jews against the rule of Rome. The Romans destroyed the Jewish Temple, putting an end to the worship and animal sacrifice (at first done in the Tabernacle, and then in the Temple) that was central to Judaism since the time of Moses. For the Christians, the destruction of the Temple was the fulfillment of Christ’s prophecy (Mt 24.1–2), and the final proof that the Lord Jesus had indeed given the Kingdom to all those who believed in Him, both Jews and Gentiles.

The Church was founded in each place as a local community. It often met in private houses, such as that of Saints Priscilla and Aquila—first in Ephesus (1 Cor 16.19) and then in Rome (Rom 16.3–5). These early congregations were led by those called bishops (overseers) or presbyters (elders) who received the laying-on-of-hands (ordination) from the Apostles (see Acts 14.23). As the Apostles themselves were called to spread the Gospel throughout the whole world, they did not serve as bishops, i.e., local leaders, of any particular Christian community in any place.

Each of the early Christian communities had its own unique character and challenges, as the New Testament writings reveal. Each church had great concern for the others, and they were all called to teach the same doctrines and to practice the same virtues, living together the same life of fellowship and sacramental worship in Christ and the Holy Spirit. Saint Luke writes that the first Church in Jerusalem “continued steadfastly in the Apostles’ doctrine and communion, in the breaking of the bread, and in prayers” (Acts 2.42). The bonds of love and faith were so strong among the first Christians that they “had all things in common, and sold their possessions and goods, and divided them among all, as anyone had need” (Acts 2.44–45).

Thus, the preaching and interpretation of God’s gospel in Jesus, the basic structure of the Church, and the essential character of Christian worship were all firmly in place by the end of the first century.