Constantine

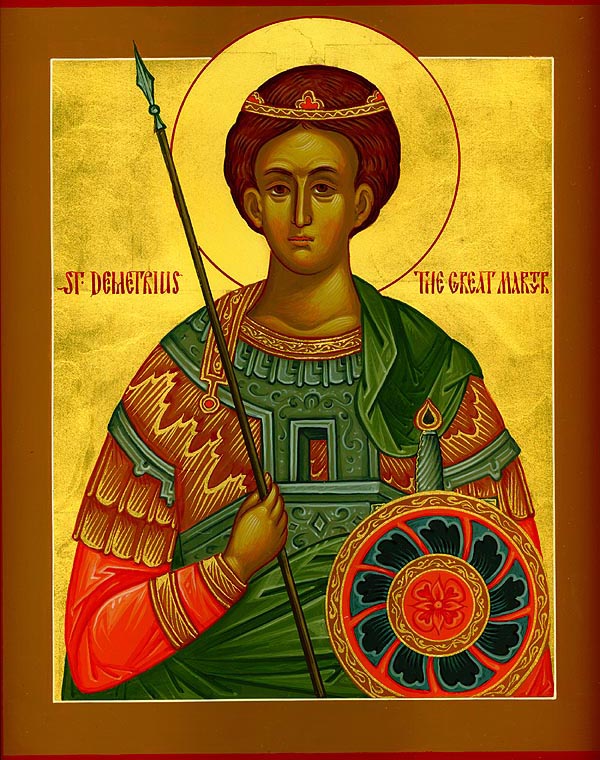

Early in the fourth century began the longest and most extensive persecution ever waged against the Church. It was started in 303 by Emperor Diocletian (r. 284–305), at the urging of his deputy emperor in the East, Galerius, who began to suspect the loyalty and valor of the Christian soldiers in the military. During this nine-year persecution, soldier-martyrs like Saint George of Nicomedia proved their courage in enduring fearsome tortures and death on behalf of the true emperor, the King of Glory. Among the other more well-known martyrs of this period are Saint Katherine the Greatmartyr of Alexandria; Saint Panteleimon of Nicomedia; Saint Demetrius the Greatmartyr of Thessalonica and his friend Saint Nestor; Saints Agapia, Chionia, and Irene of Aquileia; and the 20,000 Martyrs of Nicomedia.

After Diocletian abdicated the throne in 305, Galerius became the Emperor in the East. He continued the attack against Christianity until he was on his deathbed, when he asked the Christians to pray for him. After his death in 311, his former deputy emperor, Maximin, renewed the persecution for another year, until he was overthrown by Licinius.

Meanwhile, Constantine was proclaimed emperor in the West in York, England, in 306, upon the death of his father, the deputy emperor Constantius. In 312, as Constantine was moving with his troops towards Rome to fight against Maxentius, the tyrannical ruler there, he had a vision or a dream that dramatically changed the course of history. He saw in the sky the Cross or Labarum (Chi Rho: XP) of Christ with the words, “In this sign, conquer.” He placed this Christian symbol on his troops’ tunics and shields, and they won the battle—known as the Battle of the Milvian Bridge.

With this Christ-inspired victory, Constantine not only became the sole emperor in the West; he also became a stronger believer in the God of the Christians. So he acted very quickly to bring the era of persecution of Christians to an official end. In February of 313, Constantine met Licinius, the ruler of the Eastern half of the empire, in Milan. Together they issued the Edict of Milan giving freedom to Christians to practice their Faith in the empire—as well as affirming general religious freedom for everyone. Now recognized as a legal entity, the Church expanded and flourished greatly during the 4th century—so much so that in the last decade of the century, Emperor Saint Theodosius the Great (r. 379–395), with advice from Saint Ambrose, Bishop of Milan (c. 339–397), made Christianity the official state religion of the Empire.

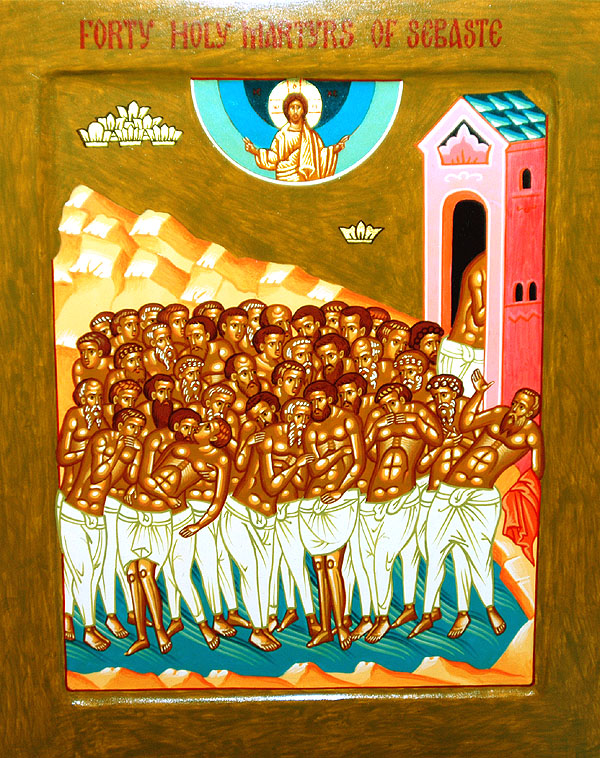

In about 320, the eastern emperor Licinius began persecuting Christians in the military. The Forty Martyrs of Sebaste and the Greatmartyr Theodore Stratelates died for Christ in this time. Partly because of this betrayal by Licinius of the Edict of Milan, Constantine led his troops against him. By 324 Constantine had defeated Licinius, thus becoming sole emperor of the whole empire, both East and West.

Excerpts from the Edict of Milan

When with happy auspices I, Constantinus Augustus, and I, Licinius Augustus, had arrived at Milan, and were enquiring into all matters that concerned the advantage and benefits of the public, among the other measures directed to the general good, or rather as questions of highest priority, we decided to establish rules by which respect and reverence for the Deity would be secured, i.e, to give the Christians, and all others, liberty to follow whatever form of worship they chose, so that whatsoever divine and heavenly powers that exist might be enabled to show favor to us and to all who live under our authority. . . . we have given the said Christians free and absolute permission to practice their own form of worship. . . .

With regard to the Christians, we also give this further ruling. In the letter sent earlier to Your Dedicatedness, precise instructions were laid down at an earlier date with reference to their places where earlier on it was their habit to meet. We now decree that if it should appear that any persons have bought these places either from our treasury or from some other source, they must restore them to these same Christians without payment and without any demand for compensation, and there must be no negligence or hesitation. . . . All this property is to be handed over to the Christian body immediately, by energetic action on your part, without any delay.

And since the aforesaid Christians not only possessed those places where it was their habit to meet, but are known to have possessed other places also, belonging not to individuals but to the legal estate of the whole body, i.e., of the Christians, all this property, in accordance with the law set forth above, you will order to be restored without any argument whatever to the aforesaid Christians.

In the next year Emperor Constantine had a dream which he believed was given to him by God, directing him to build a magnificent Christian city at the site of the ancient town of Byzantium. Very strategically located at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, this city was officially dedicated in 330 as Constantinople (meaning “City of Constantine”), the new imperial capital. The emperor helped to build churches there, in particular the Church of the Holy Apostles, where he was buried upon his death in 337.

Another highlight of his reign was the visit of his mother, Saint Helen, to Palestine. There she made pilgrimage to the holy sites of Christ’s life. With divine guidance she made a discovery that inflamed the heart of the Christian world. Near the hill of Golgotha outside Jerusalem, she found the True Cross on which Christ was crucified. Constantine helped to build churches at some of these sites, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and Jerusalem quickly became a great center of pilgrimage for the entire Christian world.

The era of Constantine is sometimes seen in the West as the beginning of the corruption of the pure Christianity of the Early Church. During the fourth century, millions more people become Christians, many of whom may not have had the spiritual fervor of the early Christians. But for Orthodox Christians, the great importance of Constantine is that with his conversion to the true faith, what was only a seemingly impossible dream now became possible: namely, the conversion of the entire society—the whole empire—to Christ.

Constantine not only allowed the Church to operate freely; he also specifically helped it in many ways. He restored or made restitution for properties that Christians had lost during the Diocletian Persecution. He sponsored copies of the Scriptures to be produced. He helped many churches to be built. He entrusted the Church with substantial amounts of tax revenue to use for charitable work. He gave the Lateran Palace to the bishop of Rome to be his residence. And he made it easier for the populace to attend church on Sunday by making it a weekly holiday—thus forming, along with Saturday (the Sabbath), the weekend which we still have. This was not an arbitrary decision on his part; rather, he was honoring Sunday as “the Lord’s Day,” the day of Christian worship from the very beginning (Rev 1.10; Acts 20.7; 1 Cor 16.2; also Saint Justin Martyr, First Apology 67).

In addition, Constantine began to bring Christian influence into the law code. In 316 a law was passed prohibiting branding criminals on the face “because man is made in God’s image.” He ended the special taxation of single people (which Augustus Caesar had instituted to try to reverse a downward trend in the population of Italy in his day), thus honoring the Christian practice of consecrated virginity. Constantine also made grants of money to poor families to help them support their children, thus discouraging the practice of exposure of infants by parents who felt they could not provide for them. And he exempted Christian clergy from every form of civic duty—so that, in his words, “they will be completely free to serve their own law at all times. In thus rendering wholehearted service to the Deity, it is evident that they will be making an immense contribution to the welfare of the community”” (Eusebius, History of the Church 10.5).

Another typical Western view is that Constantine initiated the process whereby the Eastern Church became subject to and dominated by the Emperor—a state of affairs called caesaropapism. In reality, while there were some notable exceptions, most of the time the Eastern Church functioned in harmony with the State in a relationship known as symphonia. In this arrangement, the Church was responsible for the spiritual welfare of the people, while the Emperor was responsible for their physical and material well-being. The Emperor had the responsibility to defend and protect the realm; thus he was also seen as defending and protecting the Faith of the realm. But this did not mean that he was dominating the Church. Rather, he was helping to assure that it could continue to function in peace.

The emperor sometimes recognized the need to help the Church to resolve internal disputes. At such times he would use his authority to summon Church councils. Thus, it was an emperor or empress who called each of the Seven Great Ecumenical Councils (called “Ecumenical” because they were received by the entire Church). But this does not mean that the State was interfering in its life. Rather, the emperor or empress acted in collaboration with Church leaders in calling these councils, and allowed the Church to reach its own decisions during the councils.

Sadly, however, some emperors did use their authority to support heretical teachings. The most prominent and grievous example is the era of the six Iconoclastic emperors in the 8th and 9th centuries.

For all of Constantine’s great efforts on behalf of the Christian Church and in promoting its influence in his vast domain, and for his own repentance and life of faith, he is revered in the Eastern Church as Saint Constantine the Great, Equal-to-the-Apostles. He and his illustrious mother, Saint Helen, are honored together on May 21. Interestingly, he is not considered a saint in the Roman Catholic Church, no doubt partly because of his permanent removal of the imperial capital from Rome to Constantinople.