Eastern Europe and Greece

In the 19th century, the traditionally Orthodox lands of Serbia, Romania, and central and southern Greece gained liberation from the Turkish yoke. The Greek Revolution broke out in February of 1821 with the invasion into Moldavia from southwestern Russia led by Alexandros Ypsilantis, who was the Captain-General of the top secret, conspiratorial Society of Friends. However, the revolt did not gain widespread popular support until one hierarch gave his blessing for it. That man was Metropolitan Germanos of Old Patras, who raised the standard of revolt on March 25, 1821; this date has been celebrated ever since as Greek Independence Day. With the reluctantly given aid of Britain, France, and Russia, the Turks were finally expelled from central and southern Greece by 1829. Northern Greece, however, had to wait until the Balkan War of 1912 to gain its freedom. And of course, Constantinople (Istanbul), Asia Minor (Turkey), and Thrace (European Turkey) remain in the hands of the Turks to this day.

The patriarch of Constantinople at the time of the revolt, Saint Gregory V (r. 1797–1798, 1806–1810, and 1818–1821), and twelve metropolitans, along with as many as 30,000 Greeks in and around Constantinople, were murdered by the Turks when the news of the revolt reached the capital. The patriarch was hung from the gates of the Church of Saint George, his headquarters in the Phanar district of Constantinople, on the morning of Holy Pascha, April 10, 1821. He is commemorated as Hieromartyr Saint Gregory V.

At a council in Nauplion in the Peloponnesus in 1833, the Church in newly liberated Greece declared herself to be autocephalous from the Patriarchate of Constantinople. This status was accepted and confirmed by Constantinople in 1850. With free Greece now under the rule of the Bavarian King Otto (beginning in 1831), the reorganized Church of Greece was structured along the lines of the Protestant State-Churches in northern Europe. Meanwhile, the patriarchal theological seminary on the island of Halki, near Constantinople, was founded in 1844.

With the liberation of Serbia and Romania from the Ottoman Turks also by about 1830, five self-governing dioceses of the Serbian Orthodox Church and two dioceses of Romanian Church were set up beyond the boundaries of the Ottoman Empire. This gave them the welcomed freedom to use the Serbian and Romanian languages in their services, after many years of enforced Hellenization of their churches under the authority of the Ecumenical Patriarch.

Within the Empire, the Bulgarian people sought and obtained permission from the Turks to have their own separate church jurisdiction in 1870. The Bulgarians also had been governed by Greek bishops appointed by the patriarch of Constantinople, and they resented the forced Hellenization of their church life.

However, in 1872, at an important Church council held in Constantinople, any attempt to establish a separate Church administration on the basis of ethnicity or nationality was officially condemned as the heresy of phyletism. When the Bulgarian Christians refused to accept this ruling, the Church of Constantinople excommunicated them, thus creating the so-called Bulgarian Schism. This rupture in relations lasted until 1945, when an independent Bulgarian Church was established within the territorial boundaries of Bulgaria as they stood at the end of World War II. In 1953 the Bulgarian Church regained her patriarchate, which had been lost in 1393 when the Ottoman Turks conquered Bulgaria.

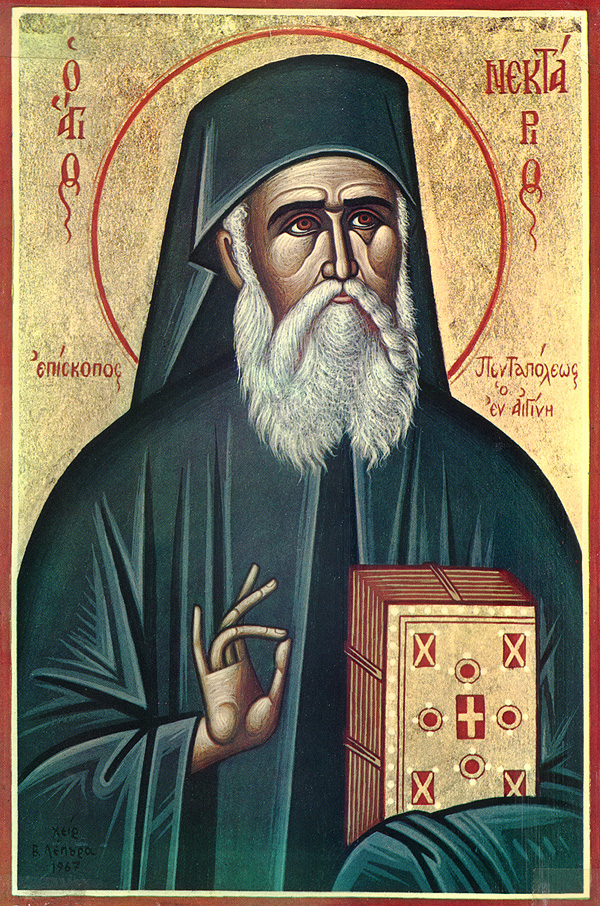

A leading saint of this era in the Eastern Church was Saint Nektarios of Aegina (1846–1920). As Archbishop of Pentapolis in Libya he was known for his evangelical preaching and manner of life, characterized by humility, simplicity, poverty, and love for the brethren. He was being groomed to succeed Patriarch Sophronios of Alexandria as head of the Patriarchate of Alexandria. However, when he was slandered by envious fellow hierarchs and others, the patriarch believed the slander and exiled him out of the Alexandrian patriarchate. He found refuge in Athens, where he served as a “holy preacher” and headed the Rizarios Academy for 15 years before retiring to the island of Aegina. There he restored and shepherded a women’s monastery. Many miracles have occurred through his relics and his many appearances to the faithful since his death.

Another remarkable saint of this period was Saint Arsenios of Cappadocia (1840–1924), an exceptionally holy priest-monk who lived in a Christian enclave in central Asia Minor surrounded by Turks. As there was no doctor in the area, everyone came to him for healing, both Christians and Muslims, and many were healed through his prayers.