Development of Theology

The third century also witnessed the emergence of the first formal school of Christian theology. It was located in Africa—in Alexandria, Egypt. Founded in about 180 A.D. by Pantaenus, a converted Stoic philosopher, the school was developed and strengthened by Clement (d. c. 215), and crowned by the outstanding theologian and scholar Origen (c. 185–254). Whereas Tertullian strongly rejected any alliance between “Athens and Jerusalem”—that is, between pagan philosophy and Christian revelation—the Alexandrians insisted that Greek philosophy was preparation for the Christian Gospel. They affirmed that the glimmers of truth discerned by the great pagan philosophers, poets, and dramatists all point to, and are fulfilled and completed by, the truth of the Christian Faith. Hence, Christianity can be seen to be the Highest Philosophy, the culmination of all human philosophical endeavor. Thus, Origen wrote to his illustrious disciple Saint Gregory the Wonderworker (c. 213–c. 270),

I desire you to take from the philosophy of the Greeks what may serve as a course of study or a preparation for Christianity, and from geometry and astronomy what may serve to explain the sacred Scriptures, in order that all that the philosophers say about geometry and music, grammar, rhetoric, and astronomy, we may say about philosophy itself, in relation to Christianity.

The work of Origen was phenomenal. He wrote numberless treatises on many themes. He is known as the “Father of Biblical Criticism” for the Hexapla, his monumental, six-fold, critical (meaning trying to determine the most accurate text) edition of the Old Testament, and for his commentaries on most of the books of the Bible. He is also known as the “Father of Systematic Theology,” mostly for his work called On First Principles, the first of its kind, in which he systematically treated all the major doctrines of the Christian Faith. In general, his work laid the foundation for virtually all subsequent theological scholarship in the Greek Church.

However, in some of his works Origen made use of various problematic Platonistic teachings as he tried to explain certain mysteries of the Faith which the Church had not yet officially clarified. In time, these Platonistic speculations led to various heresies, mostly among certain monks who considered some of these questionable teachings to be dogma. As this problem increased, by the middle of the 6th century, out of a pastoral concern to put an end to these divisive heresies, the Church took the drastic step of condemning Origen himself, as well as his erroneous teachings, at the Fifth Ecumenical Council in the year 553.

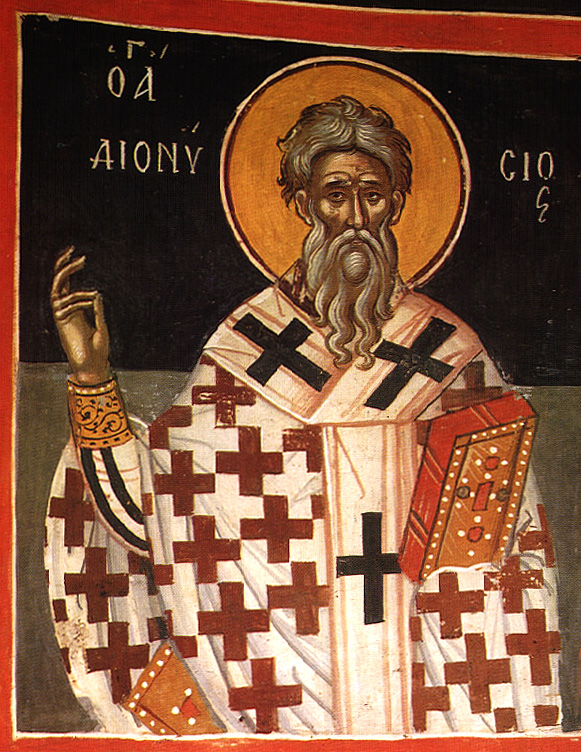

Among the major theologians of the third century who also must be mentioned are Saint Dionysius the Great, Bishop of Alexandria (d. 264); Saint Gregory the Wonderworker, Bishop of Neocaesarea in Cappadocia (d.c. 270); and Saint Methodius, Bishop of Olympus in western Asia Minor (d. 311). Saint Dionysius, the dynamic bishop of Alexandria from 247 until his death in 264, was noted for his efforts in helping to end disputes of various kinds among and within the Churches around the Mediterranean Basin. He led the opposition to the heretical teachings of Paul of Samosata, Bishop of Antioch, and may have died at the first council in Antioch that condemned Paul’s erroneous speculations about the Holy Trinity and about Christ.

It is interesting to note that when Paul did not cease his erroneous teachings, a subsequent council in Antioch, held in 268, reaffirmed the condemnation of his speculations and deposed him as bishop. However, he refused to give up the episcopal throne and residence. Finally, in 272 the Church appealed to Emperor Aurelian (r. 270–275), who had recently won back Antioch from the Kingdom of Palmyra, to remove Paul by force. This he did, after conferring with “the bishops of the religion in Italy and Rome” (as presumably impartial judges, as reported by Bishop Eusebius in his History of the Church VII.30.19), who assured him that the Church in the East had indeed acted properly in deposing Paul.

This was apparently the first time the Church ever appealed to the civil authorities for assistance. It is perhaps a sign of the Church’s growing &lquo;self-confidence” regarding its place and stature in Roman society that it would make such a request from the emperor, who just as easily could have been persecuting Christians. It also can be seen as prophetic of the alliance of the Church with the State that will gradually develop during the fourth century.

Concerning Saint Gregory the Wonderworker, it is said that upon his return to his hometown of Neocaesarea after his five years in Palestine, there were only 17 Christians; but at his death, after being bishop for about 30 years, there were only 17 pagans. Though Gregory was converted to Christianity by Origen, and though Origen was his teacher for five years, there is no evidence of Origen’s problematic, misleading speculations in Gregory’s writings.

And Saint Methodius, a prolific writer and important theologian, was one of the first Christian leaders to point out and refute various erroneous speculations in Origen’s works. Methodius’s only work which comes down to us in its entirety is called The Symposium, or the Banquet of the Ten Virgins. Interestingly, this treatise contains an especially positive understanding of marriage and marital relations, even though its overarching theme is praise for a life of consecrated virginity. He died as a martyr near the end of the Diocletian Persecution.