Prophets

There are sixteen books in the Bible called by the names of the prophets although not necessarily written by their hands. A prophet is one who speaks by the direct inspiration of God; only secondarily does the word mean one who foretells the future. Four of the prophetic books are those of the so-called major prophets: Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and Daniel.

Most scholars believe that the book of Isaiah is the work of more than one author. It covers the period from the middle of the eighth century before Christ to the time of the Babylonian exile. It tells of the impending doom upon the people of God for their wickedness and infidelity to the Lord. And it foretells the mercy of God upon His People, as well as the gentiles, in the time of His redemption in the messianic age. The famous vision of the prophet in chapter six is included in the eucharistic prayers of the Orthodox Church. Of central importance in Isaiah are the prophecies in the first part of the book, especially chapters six to twelve, concerning the coming of the Messiah-King; and the prophecies at the end of the book, about the salvation of all creation in the suffering servant of the Lord. The entire book of Isaiah is read in the Church during Great Lent, and many selections are read at the vigils of the great feasts of the Church. In the New Testament scriptures there are innumerable quotations of the prophecy of Isaiah made in reference to John the Baptist, and most especially to Christ Himself.

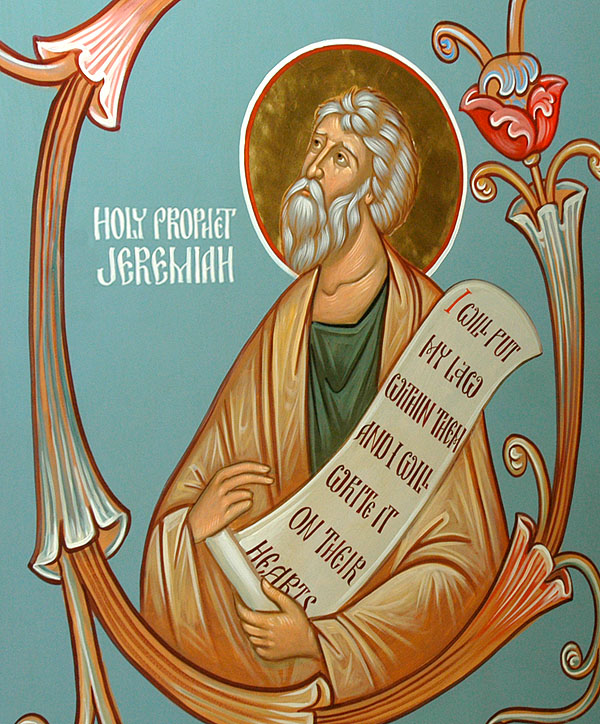

The book of Jeremiah covers the period of the seventh century before Christ and, like Isaiah, prophecies the Lord’s wrath upon His sinful people. Jeremiah, a most reluctant prophet, suffered greatly at the hands of the people and was constantly persecuted for his proclamation of the Word of the Lord. The book is referred to many times in the New Testament. The messianic prophecies of salvation in Jeremiah are often read in the festal services of the Church. The books of Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah from the apocrypha go together with this prophetic book in the Orthodox version of the Bible.

The book of Ezekiel, who was a priest as well as a prophet, is dated at the time of the Babylonian Captivity. Once again, the prophet is directly concerned with God’s righteous anger over the sins of His People, making specific reference to the presence—and the departure—of the Lord’s glory in the Jerusalem Temple. Ezekiel, however, like all of the prophets, is not without hope in the mercy of God. The moving passage about God’s resurrection of the “dry bones” of dead Israel through the breathing in of His Holy Spirit is read over the tomb of Christ at the Great Saturday service of the Orthodox Church.

The prophecy of Daniel, read in the Church at the vigil of Easter, is concerned with the faithfulness of the Jews to their God in the time of forced apostasy. Scholars consider this book among the latest written in the Old Testament, much after the time of the Babylonian captivity in which the story is placed. Central among the book’s messages is the redemption of Israel in the victorious coming of the heavenly Son of Man, who, in the New Testament, is identified with Christ. It is the apocalyptic character of the book—apocalyptic meaning that which refers to the final revelation of God and His ultimate judgment over all creation—which accounts for the placement of Daniel at a date close to New Testament times. The Song of the Three Youths which goes together with Daniel and which is placed by the non-Orthodox among the apocryphal writings, forms a genuine part of the Bible in the Orthodox Church, as do the books of Susanna and Bel and the Dragon, also part of Daniel. The Song of the Youths is part of the matinal office in the Orthodox Church.

Among the books of the so-called minor prophets, Amos and Hosea are the earliest, coming, like the first part of Isaiah, from the middle of the eighth century before Christ. Amos is the great proclaimer of the justice of God against the injustices of His People. Hosea tells of the unwavering love of God which will ultimately triumph over the adulterous harlotry of His People who unfaithfully lust after false gods. The book of Micah dates from approximately the same period and is very similar in content to Isaiah. In Micah is found the prophecy of the Savior’s birth in Bethlehem (5.2–4).

Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah are dated in the later part of the seventh century before Christ. They imitate Jeremiah, prophesying the wrath of a good and just God upon a wicked and unjust people. Like Jeremiah, they also foretell the restoration of Israel by the merciful Lord.

Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi, and perhaps Obadiah, belong to the period of the return of God’s People from exile. Zechariah is famous for the oracle of the appearance of the Savior-King, “triumphant and victorious as he is, humble and riding on an ass . . .” (9.9) which referred to Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday. Malachi, who is ferocious against the sins of the priests, is the last of the prophets before John the Baptist whose coming he foretells, as did the others, to usher in the “great and terrible day of the Lord” (3.1, 4.5) when “the Sun of Righteousness shall arise with healing in his wings” (4.2), a reference made, according to Christians, explicitly to their Lord.

The prophecy of Joel, quoted by Saint Peter in reference to the coming of the Holy Spirit on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2), belongs to the apocalyptic style of Daniel as it speaks of the final acts of God in the days of the Lord’s “great and terrible” appearance when He will execute justice and restore the fortunes of His People, delivering “all who call upon the name of the Lord” (2.31–32).

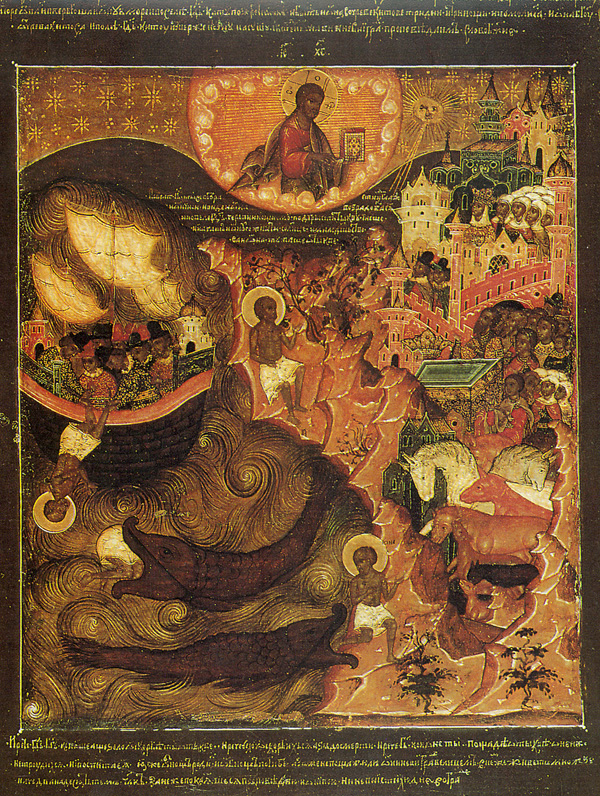

The book of Jonah is most likely a prophetic allegory intended to foretell the Lord’s salvation of the gentiles in the time of His final messianic presence in the world. It was probably written in post-exilic times. It is read in its entirety in the Church at the Easter vigil of Great Saturday as it was directly referred to by Christ Himself as the sign of His messianic mission in the world (Mt 12.38, Lk 11.29).

It must be mentioned at this point, that the variation in names found in English for the prophets, as well as for other persons and places in the scriptures, comes from the different Hebrew and Greek language traditions of the Bible. The Orthodox sources most often tend to follow the Greek. Thus, for example, Elijah becomes Elias, Hosea becomes Osee, Habakkuk becomes Avvakum, Jonah becomes Jonas, etc. Once again we must mention as well that according to Christians, the entire Old Testament finds it deepest meaning and its most perfect fulfillment in the coming of Christ and in the life of His Church.