The Saints

The doctrine of the Church comes alive in the lives of the true believers, the saints. The saints are those who literally share the holiness of God. “Be holy, for I your God am holy” (Lev 11.44; 1 Pet 1.16). The lives of the saints bear witness to the authenticity and truth of the Christian gospel, the sure gift of God’s holiness to men.

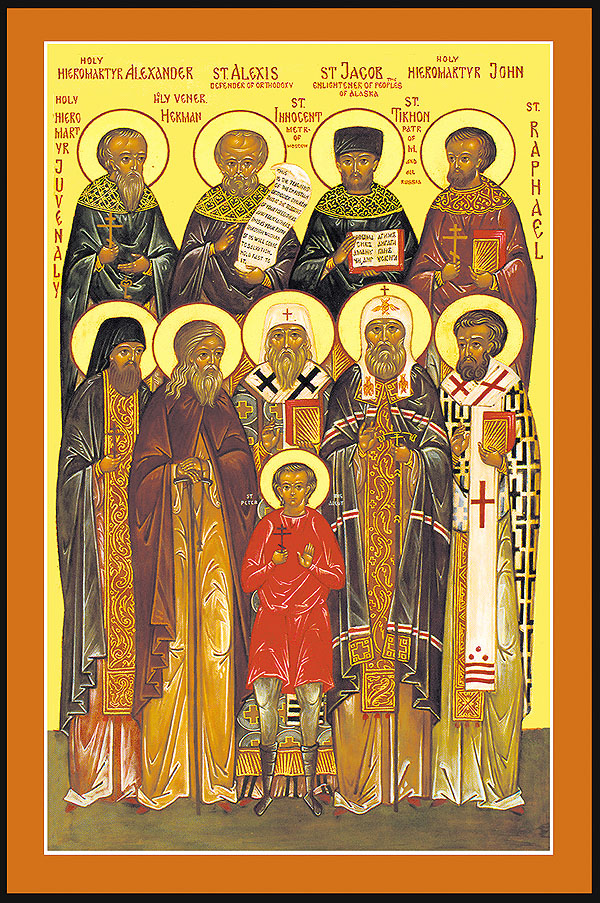

In the Church there are different classifications of saints. In addition to the holy fathers who are quite specifically glorified for their teaching, there are a number of classifications of the various types of holy people according to the particular aspects of their holiness.

Thus, there are the apostles who are sent to proclaim the Christian faith, the evangelists who specifically announce and even write down the gospels, the prophets who are directly inspired to speak God’s word to men. There are the confessors who suffer for the faith and the martyrs who die for it. There are the so-called “holy ones,” the saints from among the monks and nuns; and the “righteous,” those from among the lay people.

In addition, the church service books have a special title for saints from among the ordained clergy and another special title for the holy rulers and statesmen. Also there is the strange classification of the fools for Christ’s sake. These are they who through their total disregard for the things that people consider so necessary—clothes, food, money, houses, security, public reputation, etc.—have been able to witness without compromise to the Christian Gospel of the Kingdom of Heaven. They take their name from the sentence of the Apostle Paul: “We are fools for Christ’s sake” (1 Cor 4.10; 3.18).

There are volumes on lives of the saints in the Orthodox tradition. They may be used very fruitfully for the discovery of the meaning of the Christian faith and life. In these “lives” the Christian vision of God, man, and the world stands out very clearly. Because these volumes were written down in times quite different from our own, it is necessary to read them carefully to distinguish the essential points from the artificial and sometimes even fanciful embellishments which are often contained in them. In the Middle Ages, for instance, it was customary to pattern the lives of saints after literary works of previous times and even to dress up the lives of the lesser known saints after the manner of earlier saints of the same type. It also was the custom to add many elements, particularly supernatural and miraculous events of the most extraordinary sort, to confirm the true holiness of the saint, to gain strength for his spiritual goodness and truth, and to foster imitation of his virtues in the lives of the hearers and readers. In many cases the miraculous is added to stress the ethical righteousness and innocence of the saint in the face of his detractors.

Generally speaking, it does not take much effort to distinguish the sound kernel of truth in the lives of the saints from the additions made in the spirit of piety and enthusiasm of the later periods; and the effort should be made to see the essential truth which the lives contain. Also, the fact that elements of a miraculous nature were added to the lives of saints during medieval times for the purposes of edification, entertainment, and even amusement should not lead to the conclusion that all things miraculous in the lives of the saints are invented for literary or moralizing purposes. Again, a careful reading of the lives of the saints will almost always reveal what is authentic and true in the realm of the miraculous. Also, the point has been rightly made that men can learn almost as much about the real meaning of Christianity from the legends of the saints produced within the tradition of the Church as from the authentic lives themselves.