by His Beatitude Metropolitan Tikhon

Today is Earth Day. As the focus of this day is mostly on the climate crisis, or connections between COVID-19 and climate change, we wonder, where is the Creator, where is Jesus Christ, in all our talk about care of the Earth? In a brief reflection His Beatitude Metropolitan Tikhon helps us to refocus our hearts on the majesty of creation that we encounter in our liturgical hymns and in our actual day-to-day existence, and on Jesus Christ.

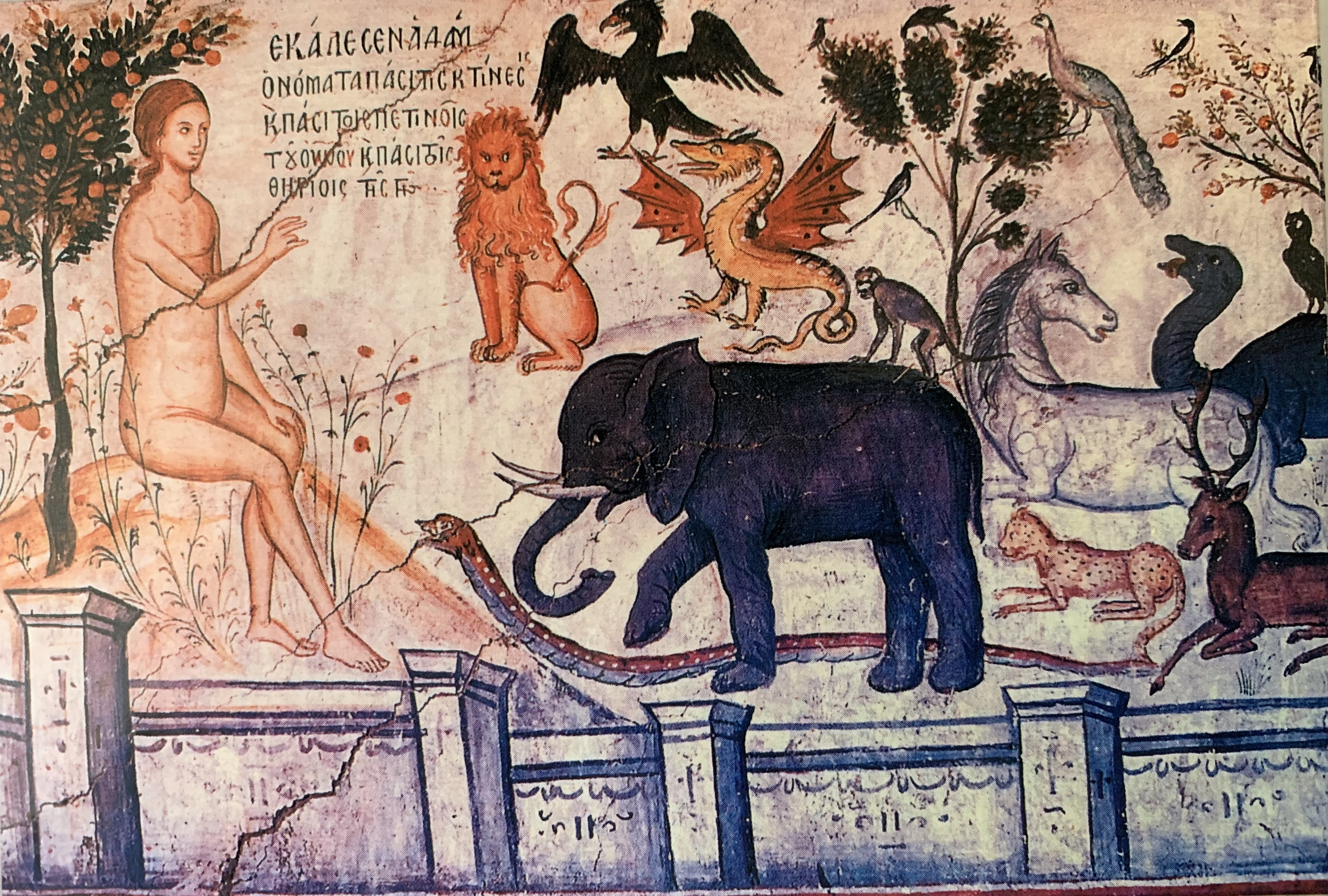

Christ is “the source of life and immortality, and the Maker of all creation, both visible and invisible,” but today, the topic of creation is too often narrowly restricted to controversies surrounding the environment, to which only polarized and politicized answers seem acceptable: is global warming real? Are humans responsible for the melting of the ice-caps? Are we protecting endangered wildlife? But the relationship of humans to the creation is a fundamental relationship which finds its roots in Paradise, where the primary task of the first created man was to tend a garden, name the animals and live off of the fruit of certain trees.

When it saw Adam leave Paradise, all of the created world which God had brought out of non-being into existence no longer wished to be subject to the transgressor. The sun did not want to shine by day, nor the moon by night, nor the stars to be seen by him. The springs of water did not want to well up for him, nor the rivers to flow. The very air itself thought about contracting itself and not providing breath for the rebel. The wild beasts and all the animals of the earth saw him stripped of his former glory and, despising him, immediately turned 1 Prayer of St. Basil the Great, first pre-Communion prayer. of what life do we speak? 36 savagely against him. The sky was moving as if to fall justly down on him, and the very earth would not endure bearing him upon its back. —St. Symeon the New Theologian.

The sacred hymns of the liturgical year overflow with references to the creation, not as a self-contained element, but always in relation to the Creator and, by extension, to humanity. In the beginning, it was creation that was first brought into existence by the Word and Spirit of God. Man, created at the conclusion of this work, and placed within this creation, as in a garden, fell and was unable to remain worthy of God’s blessing, turning away from Him through disobedience. As a result, the renewal of creation is dependent on the renewal of mankind:

[The Creator] wills that all creation serve man for whom it was made, and like him become corruptible, so that when again man is renewed and becomes spiritual, incorruptible, and immortal, then creation, too, now subjected to the rebel by God’s command and made his slave, will be freed from its slavery, and, together with man, be made new, and become incorruptible and wholly spiritual. - Saint Symeon the New Theologian

In other words, we cannot express care for the creation unless we first take care for the healing of our own bodies and souls. An “environmentalism” that is concerned only for cute and furry animals, or for the financial impact of environmental policies, falls far short of the majesty of creation that we encounter in our liturgical hymns and in our actual day-to-day existence. This applies even more directly on the local level: our diocese, our deanery, our parish, and the wider community. It is in our local community that we can have the most direct impact on the creation that we inhabit.

So let us care for the environment that we live in, recognizing the beauty and importance of God’s creation as well as the local needs in our neighborhood, our parishes, and diocesan communities, finding inspiration particularly in our monastic communities. >