The holy Elder Hieromonk Makarios (Matthew Terent'evich Sharov in the world) was born in 1802, and came from a wealthy bourgeois family in the city of Ephraimov in Tula Province. His mother was particularly devout, always walking with a prayer rope in her hands, and she raised her children in the fear of God. Following the example of his parents, Matthew Terent'evich was also devout, humble, and led a restrained life: he did not eat quickly, he read spiritual books, avoided worldly fuss, diligently visited the temple of God and often prayed to God at home. In 1822, when he was twenty years old, he finally decided to forsake the world and enter the Glinsk Hermitage under the guidance of the ever-memorable Igoumen Philaretos (Danielevskii), a man known for the sanctity of his life.

He arrived at Glinsk Hermitage when its ever-memorable restorer, Igoumen Philaretos, was the Superior. In 1828, he was enrolled in the monastery's brotherhood. As is well-known, Father Philaretos kept a close watch over the newcomers. To him, a newcomer was a child who needed spiritual milk (I Cor. 3:2; Heb. 5:12; I Peter 2:2), and the Igoumen supplied it in abundance. Into this school of piety came Matthew Sharov. In the person of Father Philaretos he found a knowledgeable spiritual guide, who had learned through personal experience, the difficulty of the path to salvation. He had studied this path to such a degree that the person under his guidance was fully assured of reaching his goal. Matthew soon felt this and entrusted himself to the wise instructor in absolute obedience. After learning Matthew's capabilities, this spiritual guide assigned him to various obediences, which did not correspond to his abilities or spiritual needs, and the young novice carried them out in a zealous manner.

At first, he was appointed to work in the monastery's apiary, where Father Igoumen often visited and watched the newcomer closely, paternally instructing him in the monastic life. His ardent performance of his duties, and his humble and willing obedience to his Elder's will predisposed Father Philaretos toward him, and he often spoke to the young struggler in a paternal way. In a short time he was so prepared that he made his monastic vows on December 16, 1833, fully aware of what he was doing. He was tonsured by his great Elder and was named Makarios.

While still a novice, he kept watch over his soul, and after becoming a monk his vigilance increased. His humility was shown in his every word, as well as in his actions, his appearance, his clothing, and in every movement. In other words, he became an image of humility in a short time. By keeping watch over his heart, he blocked the passions from entering therein with the weapon of noetic prayer. Elder Philaretos rejoiced exceedingly over his spiritual child and taught him how a true warrior of Christ must do battle with the Enemy of our salvation. The attentive disciple of this wise instructor was quickly perfected in the virtues, reaching such a level that Father Philaretos deemed him worthy of ordination.

Father Makarios tried to cleanse his heart of all earthly matters, and those things which are displeasing to God, so that he might become worthy of the grace which was given to him at his ordination. He always served with special reverence, which was noticed by those around him, even though he tried to hide it from everyone. His serving was distinguished by a profound feeling of humility, with fear and trembling before the greatness of Almighty God, before Whose altar he now stood.

Father Philaretos, seeing his disciple and spiritual son rapidly ascending the steps of perfection, wished to see him in the rank of a priest during his lifetime. Father Makarios was ordained on February 29, 1839, and his elevation to the priesthood served to make him more attentive in his spiritual life. He had it very well under the protection of his wise teacher, Father Philaretos, who always had the correct solution, his clairvoyant counsels, and his timely and necessary directives. However, on March 31, 1841, Glinsk Hermitage was deprived of its Superior, and Hieromonk Makarios lost his earthly guardian angel. But the seeds the Elder had sown were watered by his prayers from Heaven, and were strengthened by his disciple's zeal for salvation here below. Not only were these seeds not lost, but they also bore fruit a hundredfold.

Soon Hieromonk Makarios became an example for all the monks to emulate. He studied the Holy Scriptures; he had great knowledge of the exalted Christian virtues, and of the monastic virtues. He tried to put these into practice in his own life in order to be filled with the virtues indicated to us by our Lord Jesus Christ: love of God and love for one's neighbor, strict reclusion, and mortifying the body through fasting and prayer. By God's grace these became so strong in him that he wished to embrace the whole world, and to lead everyone to God. This same ardent love drew him to the service of the salvation of many people.

Father Makarios was appointed as Dean of the monastery in 1844, despite the fact that not so long ago this zealous doer of the Lord's commandments was enrolled with the state because of illness.

After assuming the difficult position of Dean of the monastery, Father Makarios devoted himself to the performance of his duty. Only his humility and his Christian love toward all led him to accept this heavy and burdensome duty, but he gave his all to it. While he was Dean, there was exemplary behavior in the monastery. Relying on the Dean's vigilance, the Superior was at peace because he knew that for the sake of holy obedience Father Makarios was ready to sacrifice his own comfort for that of all the brethren; and he also knew that they would maintain their good conduct out of respect for Father Makarios. How did Father Dean act? He divided his love in half, as it were: one half was for the Superior, whose orders he regarded as sacred; giving the other half, and himself, to the brethren. Of course, some of them did not always conduct themselves as the Superior required.

Some refused to carry out their assigned obediences out of stubbornness or self-love. Father Makarios tried to carry out their obediences himself. For example, he often made the dough for bread at night, and did other heavy work. Father Makarios tried to conceal the weakness of some of the monks from the Superior, and often he got into trouble because of this.

While covering up for the others, Father Makarios was deeply grieved by their weaknesses. He begged and begged them to correct themselves, and tried to counsel them. His instructions, coming from a heart aflame with love for God and for his neighbor, were so effective that those toward whom they were directed involuntarily gave way before the power of his words, and submitted themselves to holy obedience. Once they corrected themselves, Father Makarios was at peace concerning them. He knew that those who had been corrected would not permit any conduct which was contrary to the rules of the monastery, because they did not wish to grieve him.

Because of his position, he was obliged to come into contact with worldly people, and found ways to converse with them and to be useful to them. Beginning with the usual topics, imperceptibly he would lead the conversation toward the soul's salvation. Then he would become inspired and, as if from a pure spring, he would give spiritual drink to his listeners. Enthralled by the power of his words, they listened attentively to the ascetic and many learned the science of Christian life through him. However, while caring for the salvation of others, Father Makarios did not neglect his own. He knew how to conduct himself so that his contact with worldly people did not have an adverse effect upon him. He was rewarded abundantly when he saw that a human soul, under the influence of his tender paternal counsels, recognized its Creator.

In his cell, Father Makarios had only a few icons and books, and that was all. He did not acquire anything else. So that he would not be distracted, he glued paper over the windows of his cell, or painted them over, so that nothing could be seen through them. Prayer and solitude were his only food. Weakened by illness, he lay down on a rug and read the Psalter. At night the Elder got up to pray, supported by two crutches, and read the Holy Gospels, conversing with God for such a long time that one could not understand how he could do this, since he was ill. But God's "power is perfected in weakness" (2 Cor. 12:9).

It is said that sometimes the Elder would take a book and go into the forest. Then he would sit down somewhere to read or to pray. Finding a suitable tree stump, the ascetic would place the book on it and kneel down before it. Then his pure soul would fly to Heaven on the wings of prayer. Once, Father Makarios, as usual, went for one of these strolls in the woods, and became very tired. He sat down by the side of the road in order to rest a little, but he was so deep in meditation that he did not hear a peasant's horse-drawn wagon approaching. Suddenly, as the wagon came closer, he stood up. The horse became frightened and veered to the side. Father Makarios said, "Forgive me, brother," and bowed to him.

The peasant smiled and said, "If it were anyone else... but, since it is Father Makarios, then we shall say nothing."

This little incident shows just how much Father Makarios was respected, not only by the brethren of the monastery, but also by those who lived outside its gates.

His great ascetical labors finally caused his already fragile health to deteriorate. So, in June of 1848, he was relieved of his duties at his own request. After this, he did not leave his cell, except to go to church, and for infrequent solitary walks in the woods. At such times he was seen in the cemetery, where there was much that his humble and attentive soul knew and loved. Even though his solitary retreat in his cell was not full reclusion, all his ascetical labors were truly those of a real recluse.

One evening, two monks were going to his cell together in order to speak with him. Among the other things they mentioned about Father Makarios, one of them said, "He has locked himself in. It is easy to be saved in reclusion, because one does not behold any temptations. If he lived as we do, however, having temptations before his eyes, and if he could live as if he did not have them, then that would be a great ascetic feat indeed!"

Later, one of them had to pass by the cell of Father Makarios in order to get to his own. Father Makarios opened his door and asked him to come in. "Brother," he said, "forgive me, a sinner, and a weak one, who is unable to struggle as you do, but hides from worldly temptations in his cell. For the sake of God, forgive me."

The monk was stricken, not so much by the Elder's humility, but by the very words which the monk himself had spoken only a few moments before, and were now repeated by the Elder. This monk who had judged others made a prostration before the humble ascetic, and sincerely asked to forgiven.

The many admirers of Father Makarios, who were deprived of the great benefit of his counsels after he had locked himself in his cell, tried to come to him now in his cell, but they were turned away. Then some of them, having great faith, and who loved the Elder, asked the Superior to order Father Makarios to receive those who came to him, for the sake of obedience. As usual, the humble Elder now preferred the benefit and the will of others to his own solace, and so he opened the door of his cell to everyone. They had been waiting for a long time to hear his grace-filled words, and now that his door was open, they came to him often, and at all times, knowing that Father Makarios would always give them just the right advice and the necessary help from God. His cell was a place where many of their spiritual needs were met, and many questions were answered. From early morning until the evening, many people disclosed to him the thoughts of their hearts, weeping many warm and salvific tears of repentance. They vowed to correct themselves, and their perplexities were resolved.

The Elder’s calmness when counseling people was amazing. He listened to both the nonsensical superstitions of the common folk, and the disbelief and the foolish freethinking of educated persons. He heard the senseless complaints of a peasant woman, and the fanciful curiosity of a wealthy woman, as well as the simple stories of a peasant, and the deceitfully elegant conversations of the wise of this world. Nothing could disturb his Christian patience and his complete spiritual peace, however. He conquered all by his most profound humility. Pure joy shone on his radiant countenance, reflecting the purity of his heart. His eyes expressed his angelic meekness and inner peace. Those who entered his cell in sadness emerged in a state of happiness. The sorrowful received comfort; the despairing came out with the hope of repentance; the self-confident became humble.

As for his great piety, many people wrote to ask him for advice and guidance in the spiritual life, or about their doubts and sorrows. The loving Elder, who was always ready to help his neighbor, did not refuse to reply. As someone who had received only the most elementary education at home, he was not learned in worldly wisdom, but he attained great perfection by obeying Christ’s commandments, by his attentive study of the Holy Scriptures, and the writings of the Holy Fathers.

Many of those who came to Father Makarios with faith noticed that he had the gift of clairvoyance. One hieromonk tells us: “When I entered the monastery, I was given a cell not far from that of Father Makarios. He always had so many people waiting to see him that they stood at his door from Matins until Vespers. I often saw Father Makarios open the door, and those who were closest would fall to the floor before him. He, as though he did not notice them, would call out to someone far in the back: “John,” or “Anna, come here.” When people made their way through the crowd with difficulty, he would ask them to tell him their name, something about their life, and their reason for coming to him. Then after giving advice, he would let the person go forth in peace, and then he would call the next person in the same way. Sometimes it happened that a person who had traveled a great distance, perhaps thousands of miles, never got to see the Elder. Later, it was noticed that those he called had a greater need for his godly-wise conversation than the others.”

“Invited and blessed by Father Makarios, I often came to help out in his cell. Once, as a reward for my efforts, the Elder blessed me with a Priest’s Service Book and said, ‘Do not be proud or judge others; humble yourself and you will be a good monk. Later, you will bless others.’

“These words seemed impossible to me, because at that time I was barely able to read. Later, events revealed the truth of the Elder’s clairvoyant words, foretelling that I would become a priest.

“About two weeks after he took up residence in the tower located in the ‘Bishop’s Garden,’ I went to see him. I came to his tower and saw that there were no crowds waiting for him, only one woman who tossed some white object on the Elder’s steps as I approached. I had just reached the door, and before I had time to say the prayer, I heard the Elder’s voice: ‘Timothy, Timothy, hurry and open the door.’ The Elder could not have seen me because at the time he was lying down on his little rug with the Psalter in his hand. ‘Why do you come to me so seldom now?’ he asked.

‘Forgive me, Batushka,’ I replied. ‘I don’t have the time, because of my obedience.’

‘It is good that you have come,’ he said. Pointing to a jar of ointment in the window he said, ‘You can rub me with that. My chest hurts, and it is hard to breathe.’

“Because of his illness, the Elder’s chest was swollen. As I rubbed him I, the sinful one, thought: ‘The Elder still has some fat on him.’

“He replied to my thoughts on the spot: ‘Timothy, do you see how smooth I am? I eat so much; you can see how fat I am.’

‘Forgive me, Batushka,’ I said, struck by his clairvoyance.

“Then he said, ‘Go out and bring what is on the steps. Didn’t you see anything?’

“I forgot that I had witnessed the woman’s actions and replied, ‘No, Batushka, I did not, but bless me and I will see if there is something there, and if so, I shall bring it.’

‘No,’ he said, ‘don’t go. It isn’t necessary.’

“After finishing some of the chores which needed to be done, I said, ‘Batushka, perhaps you will bless me to go home now?’

‘God will bless you,’ he said, ‘but come to see me more often. When you go out, you will see a man and a woman standing on the ground. They are married, and live very much in harmony. His name is John, and hers is Eudokia. Tell them to come in.’

‘Bless me,’ I said.

“I went down the steps thinking: ‘Is someone here now? When I came in, there was no one around, and one cannot see from the cell because the windows are facing the forest, and besides, the Elder could not get up from the floor.’

“I went down the steps with these thoughts, and I saw a man and a woman. I thought I should ask them their names.

‘Are you here to see Father Makarios?’ I asked.

‘Yes, to see Father Makarios,’ they replied.

“I asked the man his name, and he said, ‘John.’

‘And yours?’ I asked the woman.

“She said, ‘Eudokia.’

“I asked them how they were related, and they said, ‘We are husband and wife.’

‘Go on up,’ I said.

“Then I understood the Elder’s wondrous gift of clairvoyance. I went back to my cell, not understanding why the Elder was so open with me this time. He knew, however, that this would be my last visit to him, and so he did not conceal his gift. Soon after this, he became ill. When I went to see him at the infirmary, he was unable to speak, because of his weakness. He gestured feebly for me to come close to him. Even then, when he was ill and close to death, and in pain, he still kept me in prayerful remembrance.”

Receiving those who came to him, Father Makarios with his spiritual eyes knew their future destiny, and often revealed it to them. A certain devout monk tells us the following:

“One day, my mother, my brother, and I came to Glinsk to receive Father Makarios’s blessing. As he was blessing us the Elder pointed to me and said to my mother, ‘Give this child to the Queen of Heaven, and keep this one (pointing to my brother) for yourself.’ In her simplicity, and because of her sincere faith in God’s will, as expressed to her through the Elder, she said that she was prepared to leave both of us with him. The Elder, however, repeated what he had just said.”

Later, as it happened, the older of the two boys, who had a sincere disposition toward monasticism, was proficient in that capacity. The other one, because of his leanings, could not endure monastic life.

Hieromonk A. said, “I came to Glinsk Hermitage from the Maloyaroslavets-St. Nicholas Monastery. The late Father Archimandrite Innocent, for special reasons, did not usually accept monks from other monasteries into his. When I requested to be accepted into the Hermitage, the Archimandrite refused, although he did not set a time limit on my stay at the monastery guesthouse. I lived there for three months without leaving the monastery, which had become so dear to me. In the end, I decided to go to Father Makarios for advice. The ever-memorable Elder was already sick in bed when I went to see him. Bowing to the ground before him, I described my sorrow because I could not stay and work there, since the Superior would not accept me.

“Go and ask him,” Batushka said, “and he will take you in.”

“I did as I was told, and contrary to all expectation, Father Innocent made an exception for me and took me in. Of course, it was through the prayers of Father Makarios that he accepted me.”

A certain elderly nun, a disciple of Father Makarios, describes how she entered the monastery which he indicated to her by his clairvoyance.

“Once, when I was young, I was at Glinsk Hermitage on a certain Feast Day, and attended a solemn Moleben. Among those who were serving, I saw a tall, thin Hieromonk with sunken eyes. I wanted to see his face, and just as I had that thought, he turned and looked straight at me. This, as I found out later, was Father Makarios. On another occasion, I was at Glinsk Hermitage with a little girl. I had heard a great deal about Father Makarios, but I was afraid to go see him. After the Divine Liturgy, I went back to our room in the guesthouse, and the little girl disappeared without me noticing. After a short time, she returned with a booklet: Brief Instructions for Monks. ‘I was told to give this to you,’ she said, handing me the booklet.

“After that, I wanted to see Father Makarios in person, and I asked the monk in the guesthouse to find out if he would receive me. I received this reply: ‘She must go to the monastery, and when they accept her, she may come to me for a blessing.’

“When I arrived back home, I became quite bored with everything, and could find no relief in anything I did, so I was forced to go back to Glinsk Hermitage to see Father Makarios. He received me very kindly, comforting me and ordering me to enter a monastery. When I asked which one, and where, he replied that God Himself would arrange everything.

“Returning home to my family, I regarded myself as a stranger with them. Life in the world had lost all its meaning for me. Through some acquaintances, I asked Father Makarios what I should do. He ordered them to tell me that when the time came for me to enter the monastery, I would not remain at home for even a moment. I traveled, wishing to distract myself from my terrible boredom. I visited one maiden’s monastery to pray, but did not want to enter. When I received the blessing of the Igoumeness, however, I suddenly asked to be accepted into the monastery, and she took me in. After that, I went to see Father Makarios. He received me as a father would meet a beloved child. He opened the door to his cell and told me to look things over.

“Look here, look at everything,” he said.

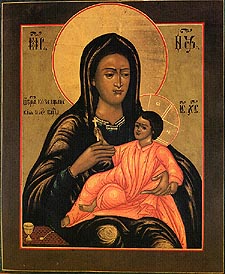

“In his cell he had only an Icon of the Mother of God “Of the Passion” (August 13), a cross, a few books, a table, a chair, and a simple wooden bench upon which was placed an old peasant’s coat. On the table there was an apple. After showing me his cell, he sat on the steps and instructed me about humility, patience, non-acquisitiveness, and in general, how a nun must live. After this, he embraced my head and kissed it, like a loving mother.1 Then he said, ‘Do you want your sister to die?’

“He was asking about my younger sister who was always sick, and whom I loved very much. I did not wish to be separated from her, however. I did not answer, and the Elder asked me again. Then, as if he was replying to my thoughts, he said, ‘You do not desire this, but it would be better if she did die. Pray about it.’ But I could not pray for my sister’s death.

“Eventually, she got better and grew up, but she had a very unhappy life. Now I regret that she did not die back then. After a year, I wanted to leave the monastery. There were many sorrows, and I did not have the patience to bear them. So, I went to Father Makarios again. He ordered me to go to another monastery and to remain there for a while. I asked to be accepted there, and I was. But I went to Father Makarios in order to find out where I must live. I returned to Batushka and he told me to go back to the first monastery, saying that God Himself had decreed that this is where I must live.

“When I returned and told Matushka Igoumeness about my trip, she would not let me go, and ordered me to make prostrations for a week (probably at trapeza) as a punishment for my willful absence. I was comforted by Father Makarios in this sorrow, and I received his wise counsel until the end of his life.”

There was a certain nun (Mother Agnes) who had money, and a nice cell; the Igoumeness loved her, and all the sisters respected her. This, however, was not good for the salvation of her soul, because "it is through many tribulations that we must enter into the Kingdom of God" (Acts 14:22).2 The Elder prayed and arranged for her to bear these saving sorrows. As a wise instructor, he did not leave her to face these sorrows without warning her ahead of time. He prepared her for all this in advance, foretelling the grief, persecution, and want that she would face. "Weep a little, weep a little! It doesn't matter why you weep," he said, "it is better than being happy."

She did not believe any of this, thinking that the Elder was joking with her. She did not realize the wisdom of the Elder's predictions until she returned to the monastery and discovered that her position had changed. His prophecy came true, exactly as he said it would. Even then, he did not leave her without help. He sent her comforting letters, saying that all this would pass, and that she would live as before. This also came true, but it was no longer harmful for her soul, because she had passed through the fire of temptation, and knew the value of worldly goods, and the fickleness of human love.

In general, the Elder consoled some people by offering a better outlook for the future; others were warned of troubles to come, preparing them in time, so that their sorrow would be easier to bear.

Large crowds of people were drawn to Father Makarios by his counsels, which came from his gift of grace, his admonitions, and by his healing of bodily infirmities. Because of this, it was sometimes difficult to move in the monastery courtyard, or near its gates, or by the cell of Father Makarios. On one occasion, people were waiting to be received, each in his turn, by the godly Elder. Hieromonk Joseph, a disciple of Father Makarios, had to make his way through the crowd. Because of the great multitude, his progress was very slow, and he was displeased. He thought, “Look at the crowd the old man has brought here. Why does he care for them? They will not let me by.”

When he walked by the Elder’s cell, he heard a tapping on the window. He went in and asked him, “Did you call me?”

“Yes, I did call you,” he replied. “Please tell me, for God’s sake, what am I to do with the people? You see how many have come and I, a wretched old man, must care for them, and they will not let me go by.”

Father Joseph then understood that the Elder had discerned his thoughts and called him in to ask him what to do with all the people. Stricken by this, Hieromonk Joseph asked for forgiveness. The Elder forgave him and said that he, “a sinner,” was not acting on his own, but in obedience to the command of the Queen of Heaven, and was doing her will. We do not know how this will was expressed: in a vision, or by the Superior’s blessing for him to receive visitors. In any case, a certain vision may have had something to do with it. Father Makarios himself told some nuns that he once had a vision on his way to church. In the monastery courtyard, and all around him, many swallows were flying. Some of them landed on his hands, and others on his shoulders, and he was able to hold them in his hands and blow on them. After that, when he was returning from church, he was carrying a cross on his head. On the roof of the cells there were many crows cawing at him. He understood that the vision of the swallows meant that he should not refuse to receive women who sought his advice. The vision where he was carrying the cross meant that this was a difficult task. The crows which cawed at him represented the brethren who complained because he received women.

Among his many spiritual gifts, Father Makarios received the gift of healing human sickness. Once, a possessed person was brought to him. He was calm, but as soon as his companions turned toward the cell of Father Makarios, the possessed man became frantic. They dragged him to the Elder by force, and Christ’s true follower laid his hands on him and healed the man by his powerful prayer to God.

His words did not have the elegance of the learned people of the world, but they were permeated with wisdom from on high, and were fervent because of his meekness and love, and so they were vibrant and effective. His words were filled with spiritual rationality, which the Fathers call the highest of all virtues.

Beyond any doubt, we know that everyone who followed the Elder’s advice received not only spiritual benefit, but they also became more successful in their worldly affairs. There are so many examples of this that it is superfluous to mention all of them here.

Sometimes the Elder’s many visitors succeeded in getting him to accept some small gift (which did not happen often). He sent all of these to the Superior, however, without pausing for a moment. Upon his death, only a small coin was in found in one of his books, because he used it as a bookmark and then forgot about it. The Elder only kept incense and candles, which he used in his cell.

In return the visitors often asked Father Makarios for some small thing as a blessing and memento. The Elder gave away everything he received to the pilgrims, and when he had nothing left, he would say, "What can I give you? I have nothing left but a few crusts of bread left over from trapeza."

His visitors were happy to receive even these crusts and accepted them with sincere reverence. By God's grace, these were more precious to them than gold or silver. Faith in the power of the Elder's prayer gave his things, even a crust of bread, similar power. According to the testimony of those who received them, they healed people of their illnesses.

Father Makarios, who helped everyone in their inner renewal, did not forget his closest fellow ascetics in the monastery. In all circumstances, and the attacks of the Enemy, the brethren ran to Batushka. Once, when Hieromonk Moses was stricken with spiritual sorrow, he hoped to receive comfort from Heaven by speaking with the Elder. But Father Makarios was so exhausted from receiving visitors that he could hardly breathe, so he asked Father Moses to come back to him in the morning. Father Moses left the Elder's cell with a heavy heart, and silently turned to Heaven, and his prayer was heard.

The next morning, as dawn was breaking, Father Makarios sent for Father Moses. When he came to the Elder's cell Father Makarios bowed before him and said, "Forgive me, a sinner, Father and brother, for refusing you yesterday. Last night I suffered terribly because of it." From that time forward, the Elder devoted himself completely to his disciples. They were able to come to him at any time without having to wait. They only had to say the customary Jesus Prayer at the door. After this they no longer were afraid of coming at inconvenient times, or of disturbing the Elder. His peace was in the spiritual peace of his disciples. Truly, one could say that Father Makarios was a worthy disciple of a worthy teacher: the ever-memorable Igoumen Philaretos. He in his turn became a worthy spiritual guide for others.

Among the brethren of Glinsk Hermitage, with whom Father Makarios was on especially friendly terms, was the nearly one-hundred-year-old Monk Theodotos. Elder Makarios was also the spiritual brother of the strict ascetic and Elder, Father Schema-Archimandrite Heliodoros (1797-1879). Even between these great spiritual men, however, there arose spiritual discontentment. Father Makarios, filled with love for everyone, had yielded to the requests of his many admirers, and he agreed to have some photographic visiting cards made.

Elder Heliodoros was deeply offended by this, and when Father Makarios came to visit him, he told him so. He believed that this decision of Father Makarios was inconsistent with monastic humility, and he criticized him harshly, "You are not an Elder, but an old man with a basket" (the Russian word he used refers to a large basket which peasants use to carry things). Then he explained the reason for his unusual words. Father Makarios explained that he did not act as he had from a desire to glorify himself, but because he didn't want to scorn the love of others. Father Heliodoros, however, refused to listen to Father Makarios. He said, "You did not do this according to God’s will. Bishops are luminaries, but who are you? This is the sort of thing which is done by those who do not care about a heavenly reward.

What had been done could not be changed, and this is the only reason we have the Elder's portrait. Father Makarios, however, took the stern disapprobation of Elder Heliodoros to heart. Hieromonk Pankratios, who was loved by Elder Makarios, and who learned much from him about his ascetical life, and himself had witnessed many signs of God's grace by the Elder's prayers, kept a secret journal about these things. Somehow, Father Makarios found out about it. Recalling Father Heliodoros's stern criticism, and through fear of eternal damnation, he ordered Father Pankratios to destroy all his notes. The latter did so, though much against his will.

This tireless worker for the glory of God, and for the salvation of his neighbor, did not spare his own health, sacrificing everything for the sake of others. After a time, although the inner man continued to grow, the temple of his body became weaker and weaker. He received some sort of revelation concerning his approaching death. As the Elder said later, he wished to "depart to live with the Angels in Heaven," and he desired to be tonsured into the Great Schema. He was tonsured on June 1, 1863 with the same name. To the repetition of his monastic vows he added even more to his former great works.

He attended all the lengthy services at the Hermitage as usual. Standing at the kleros3 and leaning on his crutch, he stood until the end of the service, ignoring the swelling of his legs and the festering wounds which covered his body, causing him to suffer a great deal. Just as before, he wore the mantiya and klobuk, with the Great Schema beneath. It was only rarely that he wore all the garments pertaining to the Great Schema. That is because after Elder Heliodoros was tonsured into the Great Schema, he wore all the garments of the Great Schema when he came to church. These, as we know, are adorned with many crosses. In their simplicity, some commoners made the Sign of the Cross and made prostrations before him. This disturbed and grieved the humble Elder so much that he never wore the garments of the Schema before the people again, but only the mantiya and klobuk. Elder Makarios imitated the example of Elder Heliodoros.

Disregarding his weakness, Elder Makarios served the Divine Liturgy with the same reverence as before. He slept very little now, sitting in the chair which had served him as a bed for seventeen years. After his tonsure into the Schema, he stopped corresponding with people by mail, but he received those who wished to see him and to receive his blessing, although not as many as before. Now he received almost no women. This continued until he was forced to take to his bed.

The cause of his last illness was a cold. As long as he was able, the Elder read all the Church Services in his cell (alone, or with the help of others), and when he was confined to bed by his illness, he listened attentively to the prayers being read by others. Now he began to partake of the Holy Mysteries of Christ more frequently, knowing full well that soon he would be separated from the bonds of his body. Provided with the Church’s Mysteries, and with his disciples weeping over him, he surrendered his soul peacefully and quietly on February 21, 1864, at the age of sixty-three.

As a good and faithful servant, Father Makarios did not sever his ties with the world below after he had passed into the joy of his Lord. There are several testimonials about this. The aforementioned woman Eudokia, who told the Elder all the circumstances of her life, was experiencing great sorrow. She often remembered Father Makarios and thought, “If only he were still alive, he would console me with his grace-filled words.”

That night, after she had fallen into a light sleep, she beheld a beautiful bower covered with greenery, and Father Makarios was inside. She rushed toward him, intending to tell him of her grief, but before she could do so, the Elder gave her an icon of Christ the Savior, and a small bottle of olive oil, and then he disappeared. In this case, the bottle of oil represented the oil of consolation, because by the Elder’s prayers, her sorrow soon passed away.

Here is another case. In a certain village, about four miles from Glinsk Hermitage, there lived a poor peasant with his wife and children. He became ill, so that he was not only unable to work, but he could not even walk. This sickness lasted for four years. His poor wife labored beyond her strength so that they would not all die from starvation. The man was not helped by village medications, and under the circumstances, they could not even think of getting a doctor to treat him. They were so poor that a dry crust of bread was regarded as a great mercy from God. She often bowed down before the holy Icon, broken-hearted and in tears, beseeching the Mother of God to heal her husband. One day, after praying in this manner, she fell asleep and saw a majestic Elder standing before her. “Why do you weep?” he asked.

“How can I not weep, Batushka?” and the unfortunate woman told him of her sorrow.

“Do not weep,” he told her, “but go to Glinsk Hermitage and ask the Superior to serve a Moleben to the Mother of God with a procession to the Skete, and your husband shall be healed.”4

“But how shall I do this?” the woman asked. “I have no money, not even a kopek.”

The Elder said, “You go to the Superior. He is kind, and he will do it without payment.”

Then she asked, “What is your name, Batushka?”

“Makarios,” he replied, and then he vanished.

This unusual dream made such an impression on the woman that she went to the Hermitage at once without saying anything to anyone. The first person she met was Father Gurios, the vestment-keeper, and she told him everything she had seen. Father Gurios related all this to Igoumen Innocent, who blessed for a Moleben to be served without any payment. The Moleben for the sick man’s health began, and at the end of the Akathist, the man himself entered the church and prayed with great fervor.

All those who heard the woman’s account of her husband’s hopeless illness were astonished when he came in, most of all, the wife herself. As he recounted later, the man had seen Father Makarios, whom he had known personally, in his dream. The Elder came and took him by the hand saying, “Why do you lay there? Get up and go to Glinsk Hermitage. Your wife will pray at the Skete, and you must pray as well.”

When he awoke, the man felt his strength returning, and he was able to move, but only with difficulty. Even so, he was able to get to the Skete before the end of the Moleben. Everyone who has experienced something similar will understand how great the joy of these poor peasants was. Even now, many people who knew Father Makarios, or who have only heard about him, take dust and leftover rain water from his grave stone with faith. Because of their faith, and the prayers of the ever-memorable ascetic, they receive help, by the grace of God.

On August 16, 2008, at the Glinsk Nativity of the Mother of God Hermitage, Saint Makarios was glorified for local veneration, along with the holy venerable Elders of Glinsk. His name was added to the Menaion of the Russian Orthodox Church by the decision of the Council of Bishops in 2017.

1 This unusual gesture, kissing a person on the head the way one would venerate a saint’s relic, indicates the wish that the person might also become a saint.

2 However: "Many are the afflictions of the righteous, but out of all of them the Lord will deliver them" (Psalm 33/34:19). [FrJF]

3 The area at the front of the church where the Readers and singers stand. The right and left choirs. The name is derived from κλήρος, which means "the drawing of lots." In the earlier times the Readers and singers were chosen by lots. (A Manual of the Orthodox Church's Divine Services, by Archpriest D. Sokolof. New York and Albany, 1899. Pages 18-19.)

4 At Glinsk Hermitage, on several days during the summer, there is a procession from the monastery to the Skete with the wonderworking Icon of the Nativity of the Theotokos.