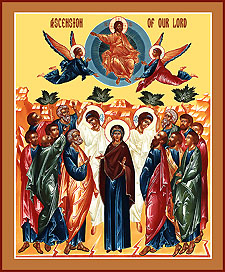

The Ascension of our Lord

“AND ASCENDED INTO HEAVEN....”

V. Rev. George Florovsky, D.D.

“I ascend unto My Father and your Father, and to My God, and Your God” (John 20:17).

In these words the Risen Christ described to Mary Magdalene the mystery of His Resurrection. She had to carry this mysterious message to His disciples, “as they mourned and wept” (Mark 16:10). The disciples listened to these glad tidings with fear and amazement, with doubt and mistrust. It was not Thomas alone who doubted among the Eleven. On the contrary, it appears that only one of the Eleven did not doubt—Saint John, the disciple “whom Jesus loved.” He alone grasped the mystery of the empty tomb at once: “and he saw, and believed” (John 20:8). Even Peter left the sepulcher in amazement, “wondering at that which was come to pass” (Luke 24:12).

The disciples did not expect the Resurrection. The women did not, either. They were quite certain that Jesus was dead and rested in the grave, and they went to the place “where He was laid,” with the spices they had prepared, “that they might come and anoint Him.” They had but one thought: “Who shall roll away the stone from the door of the sepulcher for us?” (Mark 16:1-3; Luke 24:1). And therefore, on not finding the body, Mary Magdalene was sorrowful and complained: “They have taken away my Lord, and I know not where they have laid Him” (John 20:13). On hearing the good news from the angel, the women fled from the sepulchre in fear and trembling: “Neither said they anything to any man, for they were afraid” (Mark 16:8). And when they spoke no one believed them, in the same way as no one had believed Mary, who saw the Lord, or the disciples as they walked on their way into the country, (Mark 16:13), and who recognized Him in the breaking of bread. “And afterward He appeared unto the Eleven as they sat at meat, and upbraided them with their unbelief and hardness of heart, because they believed not them who had seen Him after He was risen” (Mark 16:10-14).

From whence comes this “hardness of heart” and hesitation? Why were their eyes so “holden,” why were the disciples so much afraid of the news, and why did the Easter joy so slowly, and with such difficulty, enter the Apostles’ hearts? Did not they, who were with Him from the beginning, “from the baptism of John,” see all the signs of power which He performed before the face of the whole people? The lame walked, the blind saw, the dead were raised, and all infirmities were healed. Did they not behold, only a week earlier, how He raised by His word Lazarus from the dead, who had already been in the grave for four days? Why then was it so strange to them that the Master had arisen Himself? How was it that they came to forget that which the Lord used to tell them on many occasions, that after suffering and death He would arise on the third day?

The mystery of the Apostles’ “unbelief” is partly disclosed in the narrative of the Gospel: “But we trusted that it had been He which should have redeemed Israel,” with disillusionment and complaint said the two disciples to their mysterious Companion on the way to Emmaus (Luke 24:21). They meant: He was betrayed, condemned to death and crucified. The news of the Resurrection brought by the women only “astonished” them. They still wait for an earthly triumph, for an exernal victory. The same temptation possesses their hearts, which first prevented them from accepting “the preaching of the Cross” and made them argue every time the Saviour tried to reveal His mystery to them. “Ought not Christ to have suffered these things and to enter into His glory?” (Luke 24:26). It was still difficult to understand this.

He had the power to arise, why did He allow what that had happened to take place at all? Why did He take upon Himself disgrace, blasphemy and wounds? In the eyes of all Jerusalem, amidst the vast crowds assembled for the Great Feast, He was condemned and suffered a shameful death. And now He enters not into the Holy City, neither to the people which beheld His shame and death, nor to the High Priests and elders, nor to Pilate—so that He might make their crime obvious and smite their pride. Instead, He sends His disciples away to remote Galilee and appears to them there. Even much earlier the disciples wondered, “How is it that Thou wilt manifest Thyself unto us, and not unto the world?” (John 14:22). Their wonder continues, and even on the day of His glorious Ascension the Apostles question the Lord, “Lord, wilt Thou at this time restore again the kingdom to Israel?” (Acts 1:6). They still did not comprehend the meaning of His Resurrection, they did not understand what it meant that He was “ascending” to the Father. Their eyes were opened but later, when “the promise of the Father” had been fulfilled.

In the Ascension resides the meaning and the fullness of Christ’s Resurrection.

The Lord did not rise in order to return again to the fleshly order of life, so as to live again and commune with the disciples and the multitudes by means of preaching and miracles. Now he does not even stay with them, but only “appears” to them during the forty days, from time to time, and always in a miraculous and mysterious manner. “He was not always with them now, as He was before the Resurrection,” comments Saint John Chrysostom. “He came and again disappeared, thus leading them on to higher conceptions. He no longer permitted them to continue in their former relationship toward Him, but took effectual measures to secure these two objects: That the fact of His Resurrection should be believed, and that He Himself should be ever after apprehended to be greater than man.” There was something new and unusual in His person (cf. John 21:1-14). As Saint John Chrysostom says, “It was not an open presence, but a certain testimony of the fact that He was present.” That is why the disciples were confused and frightened. Christ arose not in the same way as those who were restored to life before Him. Theirs was a resurrection for a time, and they returned to life in the same body, which was subject to death and corruption—returned to the previous mode of life. But Christ arose for ever, unto eternity. He arose in a body of glory, immortal and incorruptible. He arose, never to die, for “He clothed the mortal in the splendor of incorruption.” His glorified Body was already exempt from the fleshly order of existence. “It is sown in corruption, it is raised in incorruption. It is sown in dishonor, it is raised in glory. It is sown in weakness, it is raised in power. It is sown a natural body, it is raised a spiritual body” (I Cor. 15:42-44). This mysterious transformation of human bodies, of which Saint Paul was speaking in the case of our Lord, had been accomplished in three days. Christ’s work on earth was accomplished. He had suffered, was dead and buried, and now rose to a higher mode of existence. By His Resurrection He abolished and destroyed death, abolished the law of corruption, “and raised with Himself the whole race of Adam.” Christ has risen, and now “no dead are left in the grave” (cf. The Easter Sermon of Saint John Chrysostom). And now He ascends to the Father, yet He does not “go away,” but abides with the faithful for ever (cf. The Kontakion of Ascension). For He raises the very earth with Him to heaven, and even higher than any heaven. God’s power, in the phrase of Saint John Chrysostom, “manifests itself not only in the Resurrection, but in something much stronger.” For “He was received up into heaven, and sat on the right hand of God” (Mark 16:19).

And with Christ, man’s nature ascends also.

“We who seemed unworthy of the earth, are now raised to heaven,” says Saint John Chrysostom. “We who were unworthy of earthly dominion have been raised to the Kingdom on high, have ascended higher than heaven, have came to occupy the King’s throne, and the same nature from which the angels guarded Paradise, stopped not until it ascended to the throne of the Lord.” By His Ascension the Lord not only opened to man the entrance to heaven, not only appeared before the face of God on our behalf and for our sake, but likewise “transferred man” to the high places. “He honored them He loved by putting them close to the Father.” God quickened and raised us together with Christ, as Saint Paul says, “and made us sit together in heavenly places in Christ Jesus” (Ephes. 2:6). Heaven received the inhabitants of the earth. “The First fruits of them that slept” sits now on high, and in Him all creation is summed up and bound together. “The earth rejoices in mystery, and the heavens are filled with joy.”

“The terrible ascent....” Terror-stricken and trembling stand the angelic hosts, contemplating the Ascension of Christ. And trembling they ask each other, “What is this vision? One who is man in appearance ascends in His body higher than the heavens, as God.”

Thus the Office for the Feast of the Ascension depicts the mystery in a poetical language. As on the day of Christ’s Nativity the earth was astonished on beholding God in the flesh, so now the Heavens do tremble and cry out. “The Lord of Hosts, Who reigns over all, Who is Himself the head of all, Who is preeminent in all things, Who has reinstated creation in its former order—He is the King of Glory.” And the heavenly doors are opened: “Open, Oh heavenly gates, and receive God in the flesh.” It is an open allusion to Psalms 24:7-10, now prophetically interpreted. “Lift up your heads, Oh ye gates, and be lifted up, ye everlasting doors, and the King of Glory shall come in. Who is this King of glory? The Lord strong and mighty....” Saint Chrysostom says, “Now the angels have received that for which they have long waited, the archangels see that for which they have long thirsted. They have seen our nature shining on the King’s throne, glistening with glory and eternal beauty.... Therefore they descend in order to see the unusual and marvelous vision: Man appearing in heaven.”

The Ascension is the token of Pentecost, the sign of its coming, “The Lord has ascended to heaven and will send the Comforter to the world”

For the Holy Spirit was not yet in the world, until Jesus was glorified. And the Lord Himself told the disciples, “If I go not away, the Comforter will not come unto you” (John 16:7). The gifts of the Spirit are “gifts of reconciliation,” a seal of an accomplished salvation and of the ultimate reunion of the world with God. And this was accomplished only in the Ascension. “And one saw miracles follow miracles,” says Saint John Chrysostom, “ten days prior to this our nature ascended to the King’s throne, while today the Holy Ghost has descended on to our nature.” The joy of the Ascension lies in the promise of the Spirit. “Thou didst give joy to Thy disciples by a promise of the Holy Spirit.” The victory of Christ is wrought in us by the power of the Holy Spirit.

“On high is His body, here below with us is His Spirit. And so we have His token on high, that is His body, which He received from us, and here below we have His Spirit with us. Heaven received the Holy Body, and the earth accepted the Holy Spirit. Christ came and sent the Spirit. He ascended, and with Him our body ascended also” (Saint John Chrysostom). The revelation of the Holy Trinity was completed. Now the Spirit Comforter is poured forth on all flesh. “Hence comes foreknowledge of the future, understanding of mysteries, apprehension of what is hidden, distribution of good gifts, the heavenly citizenship, a place in the chorus of angels, joy without end, abiding in God, the being made like to God, and, highest of all, the being made God!” (Saint Basil, On the Holy Spirit, IX). Beginning with the Apostles, and through communion with them—by an unbroken succession—Grace is spread to all believers. Through renewal and glorification in the Ascended Christ, man’s nature became receptive of the spirit. “And unto the world He gives quickening forces through His human body,” says Bishop Theophanes. “He holds it completely in Himself and penetrates it with His strength, out of Himself; and He likewise draws the angels to Himself through the spirit of man, giving them space for action and thus making them blessed.” All this is done through the Church, which is “the Body of Christ;” that is, His “fullness” (Ephesians 1:23). “The Church is the fulfillment of Christ,” continues Bishop Theophanes, “perhaps in the same way as the tree is the fulfillment of the seed. That which is contained in the seed in a contracted form receives its development in the tree.”

The very existence of the Church is the fruit of the Ascension. It is in the Church that man’s nature is truly ascended to the Divine heights. “And gave Him to be Head over all things” (Ephesians 1:22). Saint John Chrysostom comments: “Amazing! Look again, whither He has raised the Church. As though He were lifting it up by some engine, He has raised it up to a vast height, and set it on yonder throne; for where the Head is, there is the body also. There is no interval of separation between the Head and the body; for were there a separation, then would the one no longer be a body, nor would the other any longer be a Head.” The whole race of men is to follow Christ, even in His ultimate exaltation, “to follow in His train.” Within the Church, through an acquisition of the Spirit in the fellowship of Sacraments, the Ascension continues still, and will continue until the measure is full. “Only then shall the Head be filled up, when the body is rendered perfect, when we are knit together and united,” concludes Saint John Chrysostom.

The Ascension is a sign and token of the Second Coming. “This same Jesus, which is taken up from you into heaven, shall so come in like manner as ye have seen Him go into heaven” (Acts 1:11).

The mystery of God’s Providence will be accomplished in the Return of the Risen Lord. In the fulfillment of time, Christ’s kingly power will be revealed and spread over the whole of faithful mankind. Christ bequeathes the Kingdom to the whole of the faithful. “And I appoint unto you a Kingdom as My Father has appointed unto me. That ye may eat and drink at My table in My Kingdom, and sit on thrones judging the twelve tribes of Israel” (Luke 22:29-30). Those who followed Him faithfully will sit with Him on their thrones on the day of His coming. “To him that overcomes will I grant to sit with Me in My throne, even as I also overcame, and am set down with My Father in His throne” (Rev. 3:21). Salvation will be consummated in the Glory. “Conceive to yourself the throne, the royal throne, conceive the immensity of the privilege. This, at least if we chose, might more avail to startle us, yea, even than hell itself” (Saint John Chrysostom).

We should tremble more at the thought of that abundant Glory which is appointed unto the redeemed, than at the thought of the eternal darkness. “Think near Whom Thy Head is seated....” Or rather, Who is the Head. In very truth, “wondrous and terrible is Thy divine ascension from the mountain, O Giver of Life.” A terrible and wondrous height is the King’s throne. In face of this height all flesh stands silent, in awe and trembling. “He has Himself descended to the lowest depths of humiliation, and raised up man to the height of exaltation.”

What then should we do? “If thou art the body of Christ, bear the Cross, for He bore it” (Saint John Chrysostom).

“With the power of Thy Cross, Oh Christ, establish my thoughts, so that I may sing and glorify Thy saving Ascension.”

Originally published in Saint Vladimir’s Seminary Quarterly, Vol. 2 # 3, 1954.

Used with permission.